Mystagogia (13)

The Way of the Hero - Portals & Desire: Donnie Dark on Predestination, Free Will, and What It Takes to Be a Hero

A lot of time has passed since I have written in this series “Mystagogia,” and it may be beneficial to the reader to go back and read the series, or at least, the previous entry - Mystagogia (12) - where I explain the basics of the film Donnie Darko.

Mystagogia was, in the ancient world, a time period whereby Christians were trained in the faith through learning the mysteries of the Sacraments (baptism and eucharist). Literally, it means something like “to lead through the mysteries.” This substack series, Mystagogia is my attempt at re-sacramentalizing our world after we have had it wrecked by the mechanics of living in it.

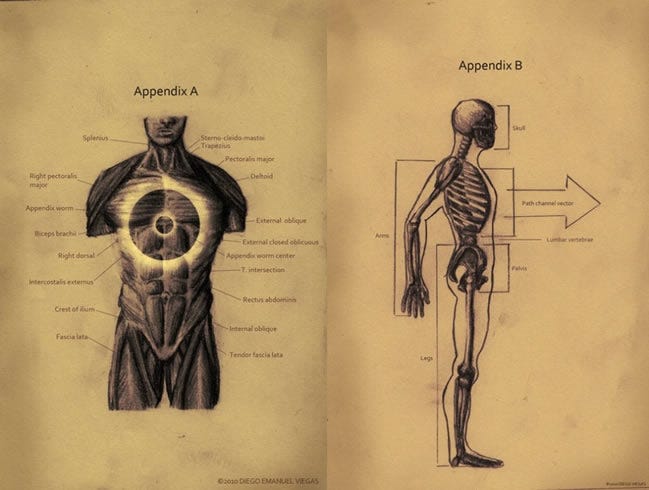

Of the three spiritual forces at work in Donnie Darko’s Tangent Universe, he seems to be most intrigued by the Cult of Lit-Sci. In a very critical scene, Donnie is struggling to make sense of his mission as the Living Receiver, he approaches his science professor (played by Noah Wyle) to discuss time travel, portals and pre-destination vs. free will. Specifically, Donnie has witnessed a portal (the film calls them “vectors”) emitting from his chest and moving toward his next destination. Donnie has read about these protrusions in the Appendix of Roberta Sparrow’s book “The Philosophy of Time Travel” (PoTT).

See below: Image 1 is from the book / Image 2 is the portal Donnie sees in the film.

Image 1.

Image 2.

His conversation with his Science Professor, although relatively brief, traces many classic questions related to God and destiny. Specifically, Donnie seems to be wrestling with pre-destination of outcomes verses the notion that “God” determines all pathways as well as outcomes. Donnie presses this issue with his science professor (who has given him a copy of Stephen Hawkin’s book “A Brief History of Time”). The conversation ends with his professor telling him that he can no longer discuss this matter with Donnie, for fear of losing his job. Donnie is frustrated. For obvious reasons he cannot trust the Cult of Jim Cunningham (the pseudo religious / self-help spiritual force), nor can he abide the Cult of Sparkle Motion (the entertainment distraction force that enthralls the entire town). And now, he cannot rely on the Lit-Sci Cult (the “intellectual” spiritual force that promises the knowledge needed to save society).

In a forthcoming post, I will discuss a fourth force pulling at Donnie - his therapist, Dr. Lillian Thurman (played by Katherine Ross). Dr. Thurman is able to actually care for Donnie in a humane and loving way. But we must set this aside for a later discussion. For now, our concern is that the 3 spiritual forces that are available to Donnie (and everyone else in Middlesex) fail him. He ultimately rejects them all.

It is an important feature of our exploration of Donnie’s Tangent Universe, to note that these spiritual forces resemble similar spiritual forces at work in our own Primary Universe.

(1) The Cult of Jim Cunningham - In the Tangent Universe of Donnie Darko, these pseudo-religious forces promise personal success, personal fulfillment, personal wealth, personal prosperity, some vague and surface notion of “happiness”, and the individual flourishing. They mirror religion and self-help culture in this late stage of American life of our own Primary Universe. A notable character defect in these cults is that they invite members to hyper fixate upon themselves and their own welfare, thereby training them to never look outward to the fate of their neighbors. Another notable defect is that the self-help guru(s) are notoriously full of… excrement. They may abide perfectly by the self-help rules they set for their assemblies, but, as Jesus pointed out to his followers, “…you can tell them by their fruit.” - and their fruit is typically the aggrandizement of themselves and the institutions they build (rather than say, the welfare of the poor or hurting or helpless). Additionally, attempts to re-orient them (or the institutions they build) outwardly toward the welfare of the poor or hurting or helpless, are typically met with resistance, or at least the complaint that such things are “negative.”

(2) The Cult of Lit-Sci is that typically progressive cohort of wannabe intellectuals who love to appeal to gnosis / knowledge as a trump card in the never-ending culture war, that despite all their supposed brilliance, they never seem capable of winning. A stunning feature of the Cult of Lit-Sci in our Primary Universe is the pride they award themselves in merely “being right” while turning a blind eye to the root causes of their enemy’s ignorance (usually economic in nature). Another stunning feature of the Cult of Lit-Sci is that they seem incapable of acknowledging that they are merely individualists at the other end of the worldview spectrum (see, Ms. Farmer’s “Love/Fear” spectrum from the film). They no more care for the members of the Jim Cunningham cult, than do the Jim Cunningham cult members care for them. Donnie, at least, cares about them all.

(3) The Cult of Sparkle Motion is that enthralling force of entertainment that dulls our senses and distracts us from the inner pain the outer world has wrought upon our hearts, minds and souls. Sparkle Motion is a crucial part of Donnie Darko’s Tangent Universe, to say nothing of our own Primary Universe. Sparkle Motion is the NBA, the WWE, Taylor Swift, the Super Bowl, the Lakers, the Country Music Awards, the Oscars, the Grammys, the Emmys, the lake trips, and Cabo trips “that don’t last forever,” the Florida getaways, the BMW’s and Benzes, the full sized SUV’s and F-350’s not-driven-by-farmers, the latest fashion trends, the Patagonia and North Face swag, the Nike shoes, the Prada, the Gucci, and the Versace. To quote Kendrick Lamar, “Take all that designer stuff off and what do you have?”

All three of these forces, (and specifically the one he actually identified with - the Lit-Sci cult) have failed him. He must now set about on his struggle with “God” all alone. The theological discovery that Donnie was hinting toward in his conversation with Professor Monnitoff, was a notion about free will and pre-destination. What if the usual bifurcation of these two things is false? What if, somehow, both are true? Here Donnie is very close to traditional orthodoxy (not only Christian orthodoxy, but classical theistic, philosophical and metaphysical orthodoxy of the most ancient variety).

If I may, allow me to note something a bit parenthetical. Believing this - that human agency consists in both free will and pre-destination - ultimately requires one to be a universalist. This is a conversation for another day (and a completely different Substack series altogether), but hang with me here - or rather, hang with Donnie. Donnie, having experienced this phenomenon of “portals” or “vectors,” now understands a new possibility; that perhaps God pre-determines fates and directs us along paths toward those fates, all while providing people freedom of choices within these destinies and vectors.1 Again, both in real life theological terms and within the bounds of the film, this ultimately makes God the savior of everyone. Donnie’s notion of free will and pre-destination undercuts all our preconceived notions about what these concepts entail.

Why Any of This Matters: or, My Definition of the “Hero”

So why does any of this matter? Why are we chasing white rabbits down rabbit holes? Why all the talk of Donnie Darko, pre-destination, free will, human agency, God, time travel, portals and the like? Let’s step back a bit and contextualize this in the framework of the entire Mystagogia series.

Donnie Darko is our emblematic “hero.” The path he takes in the Tangent Universe is a path that some people of great courage take in our own primary universe. Unlike Sherrif Ed Tom Bell (our emblematic Conservative) who can only dream of a fictional past, and unlike Nathan Bateman (our emblematic progressive) who can only dream of a mythical future, Donnie Darko isn’t seduced by any such dreams. He is our emblematic hero because he is an iconoclast. He tears down the Cults of Jim Cunningham, of Lit-Sci, and of Sparkle Motion. He rejects their offers as a worthy path to take. To put in perspective, by way of review, Donnie Darko refuses both the Way of the Conservative, and the Way of the Progressive. He chooses the Way of the Hero, instead. But what exactly are we calling a “hero" in this instance?

Wormsley Common | Gotham City | Middlesex, VA | Jerusalem

Here, I need to be very nuanced. A hero (at least for the purposes of developing my Mystagogia) is first-and-foremost an iconoclast; specifically, a hero is an iconoclast in the mold of Graham Greene’s Destructors as referenced in the film.

- Wormsley Common (circa 1954)

The short story, The Destructors, by Graham Greene, first appeared in a British photojournalism periodical called “Picture Post” in 1954. The story is set in post-war England and surrounds the destruction of a house that survived the blitz (Germany’s bombing campaign against England in the early 1940’s). The protagonist, if you can call him that, is a boy named Trevor who is the leader of a band of boys known as the “Wormsley Common Gang.” Trevor and the Wormsley Gang plot to destroy the house of a man they call “Old Misery” (Mr. Thomas). They plan on carrying out this destruction-as-a-form-of-creation when Old Misery is away on vacation, organizing to destroy the house from the inside out.

While they are busy carrying out their tour de force of calamity, Old Misery returns early from his holiday and startles the gang. Trevor instructs the boys to lock Old Misery in the outhouse, insisting that they finish the job while he is locked away. As they continue their work, they discover a mattress that is filled with money. Trevor has them the money on fire. The final act of destruction comes when they use a lorry to pull a structural support post from the corner of the house, causing it to fall. Old Misery is forced to watch this unfold as the driver of the lorry laughs uncontrollably at the scene.

What is critical about this short story, for our purposes, is brought to life by a scene from Donnie Darko:

This scene gestures toward my definition of a hero: someone who is an iconoclast, challenging and tearing down icons and idols that hold the rest of the world enthralled. I do not make a judgment (yet) about whether such a hero is good or bad. Only that their actions are heroic in the sense of their aims are ultimately salvific of people they regard to be enslaved in some way. They want to set people free.

Trevor and the Wormsley Common Gang are iconoclasts. Set in postwar England, Old Misery’s estate is a living reminder of the glory of empire. Those visions of imperialism still hold their elders enthralled. They are determined to tear it down. They use destruction “as a form of creation” to see what takes the place of whatever idols are currently on the throne. They don’t have a lot invested in what happens next. They simply know that the icons and idols that are currently on the throne need to be deposed.

- Gotham City (circa 2008)

The Destructors is reminiscent of another scene from a more modern story: Batman. Of all the film renderings of the Batman story, perhaps none is more terrifying than Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight (2008). In this installment of the series the Joker is threatening to upend not just Gotham, but even the notorious gang rule over Gotham, with anarchist style violence. In one compelling scene, The Joker takes all of the money collected from all of the collective mafia bosses and lights it on fire. What is at once interesting and terrifying about Heath Ledger’s portrayal of The Joker, is that his aims are not without a justifying narrative. His anarchy is a direct response of the failure of both Gotham’s institutions and the failure of the mafias to restore justice to the oppressed people they used to serve. Joker intends to set the entire system ablaze and see what emerges in its place.

What is particularly interesting in drawing our attention to Nolan’s The Dark Knight is that the typical hero/villain dichotomy is temporarily reversed. Very clean renderings of Batman regard Bruce Wayne as a hero and the Joker as a tidy opposite. In Nolan’s re-telling those lines are blurred. First, the mafias that arose in response to the oppressed boroughs of Gotham, in order to serve and secure them, have turned predictably rotten. Secondly, the established institutional forces entrusted to protect and serve all of Gotham are likewise infested with rot. Unlike the mafia bosses, the Joker has no interest in personal riches or self-aggrandizement. And there is just a tinge of the Joker’s justifying logic that makes sense in response to the tragic failure of the Gotham police. The Joker is an anarchist and an iconoclast. His justifying logic is that all systems are rotten and need to be brought down. Iconoclasm.

- Middlesex, VA (circa 1988)

Donnie Darko is one such iconoclast. He challenges Jim Cunningham in the most publicly spectacular fashion possible - calling him “the anti-Christ” in front of all of his followers. He burns Jim Cunningham’s house to the ground exposing a devastating truth about Jim as a child trafficker (upending his cult). He takes an axe with him to the school in the middle of the night at bursts the water main flooding the school, and then leaves the axe miraculously lodged in the skull of the giant metal bulldog (school mascot), symbolizing his fight against school's controlling power over the hearts and minds of the children. And of course, he is the only member of Middlesex (except for Gretchen, who herself even falls asleep) who refuses to attend the Sparkle Motion exhibition.

Before you recoil at the idea of a “hero” being guilty of property damage of violence of any kind, let’s contextualize (again). The purpose here is to point out that the world affixes our collective attentions to two primary “ways” of navigating our world. First, the Way of the Conservative, seeking to restore the glory of days gone by, and secondly, the Way of the Progressive, seeking to make a world of our own making, free from the trappings of the past. I have established in my Mystagogia, why neither of these “ways” will serve us. And before moving on to something like a traditional “third way,” I felt the need acknowledge and honor another, less recognizable “way” - the Way of the Hero. Yes, Trevor and Gang of Wormsley, the Joker of Gotham City, and Donnie Darko of Middlesex, all commit property damage in a (sometimes) demented quest for justice.

But then again…. so did Jesus of Nazareth.

- Jerusalem (circa, 33 CE)

In a rather classic and universally known scene from the gospels, Jesus sits and fumes for days at the “money changers” in the Temple courts. It is time for the Passover, and the poor country folk have travelled there from many regions and brought with them their very best cattle to offer as a sacrifice in the Temple. Rather than welcoming them and assisting them in their service of God, the authorities tell the people that their offerings are not good enough or pure enough. But for the “low low price of just $59.99” or what-have-you, they can upgrade to this calf or that donkey, this goat or that sheep, etc. Jesus is absolutely livid. The Temple authorities have turned a sacred ritual and site into a place to turn a profit. He fashions a whip (something that apparently takes several days), enters the Temple courts to drive out the money changers, empties the cages where all the sacrificial animals are kept, and turns over all the tables thus scattering the money (something that apparently took hours). Ask yourself, is this Jesus a hero?

Heroes and Villains: More Donnie Darko, Less Joker

Donnie Darko is honestly a more interesting hero than either the great Graham Greene’s Wormsley Gang or the Joker. There is some quality about Donnie - he is, like Jesus, identifiably kind and compassionate. The aims of his anarchy are upsetting, and perhaps damaging, but freeing, nonetheless.

It might be helpful, if for no other reason than to free me from the accusation of advocating violent anarchy, to discuss the thin line between hero and villain. I can only hope that most of it is rather self-explanatory. The Joker, in Nolan’s The Dark Knight, blows up a hospital that may or may not be evacuated. Donnie doesn’t kill anyone - in fact, he ends up sacrificing his life in the Primary Universe so that the Tangent Universe can collapse and everyone be saved. However, it is perhaps wise to attempt some degree of precision. In my definition, the Way of the Hero is defined as someone who is an iconoclast, challenging and tearing down icons and idols that hold the rest of the world enthralled.

Of course there can be in this sense, “good heroes” and “bad heroes” (villains). And of course I am preoccupied here with the good sort. I only want to say that the good sort and bad sort can only be worked out in the “how” of what they do (ethics). The hero of my definition is by default somewhat of an ethical agnostic, and perhaps even an ethical atheist in that he/she has rejected the given notions of acceptable means. Their courage rests in both deciding to reject given norms/ways and in deciding to act as an iconoclast. The blurring of lines between “good heroes” and “bad heroes” perhaps exemplifies how treacherous the Way of the Hero is. Donnie, in my view, is a good hero because he wrestles with not just what to do as an iconoclast, but with how to do it. There is some concoction of courage and attempted wisdom.

Back to Donnie Darko’s Understanding of Fate and Free Will

This brings me back to Donnie’s wrestling with pre-destination and free will. He is coming to understand that this Tangent Universe is a threat, and that to save everyone he must challenge and overthrow that world along with its enthralling spiritual forces (the Cult of Jim Cunningham, the Cult of Lit-Sci, and the Cult of Sparkle Motion). Donnie ultimately comes to see all of Middlesex’s fate lumped together: he will save them all. But to do that he must go the lonely, if courageous, path of the iconoclast. This is the path of his “vector” and his ultimate destiny.

Donnie Darko is thus someone who, prior to any action, has wrestled immensely with:

Accepted social norms

Given paths/ways (The Way of the Conservative, or The Way of the Progressive)

Cults, or Spiritual Forces (Jim Cunningham, Lit-Sci, Sparkle Motion)

His own purpose, identity, calling - in other words, his own destiny

God’s will and the makeup of the universe/world we inhabit

Donnie Darko, unlike our emblematic conservative Sheriff Ed Tom Bell, and unlike our emblematic progressive Nathan Bateman, is a hero. He refuses the ways given to him and instead seeks their exposure and destruction. Donnie Darko, the iconoclast. Donnie Darko, the hero.

Again, this is a conversation for another day. Perhaps one day I shall argue this point in a self-contained series. For now, I can only point out that this is technically speaking (despite what you may believe (or more appropriately) what some modern preacher told you, this is Christian Orthodoxy. For the first 500 years of Christianity, virtually all Christians believed that what God had accomplished in Christ was nothing less than the salvation of all humans (logoi) in the one Messiah (the Logos). There are too many interesting points to be made here. For now, I can only refer you to the Third and Fourth Meditations in David Bentley Hart’s book That All Shall Be Saved, to understand why this argument of mine is philosophically airtight, to say nothing of its theological and biblical soundness.